Good morning, my name is Os and today I’d like to talk to all of the scientists in the room about what we mean by ‘political’

(screaming, the sound of overturning chairs, a door slamming shut)

Seriously, though: we talk about ‘political’ a lot right now. For some scientists (social or natural) this is their first time doing so: for others, events like the March for Science and budget woes under Trump are the latest in a long line of advocacy work and engagement. The problem is that when we talk about ‘political’ between ourselves, we seem to be using three different definitions:

- partisan political: something is political if it relates consistently to a particular political party. A campaign against positions that come from the GOP is partisan political.

- coloquial political: something is political if it relates to something legislative, or based on formal-power-structures. A campaign against NSF funding cuts is coloquial political, regardless of who’s proposing the cuts.

- academic political, which in a scientific context might also be referred to as Science, Technology and Society (STS) political: something is political if it has impacts on, or is impacted by, the exercise of power within society. NSF funding cuts and GOP positions are political - but so are research ethics, sexual harassment and racism within science, and the outcomes of our work as scientists.

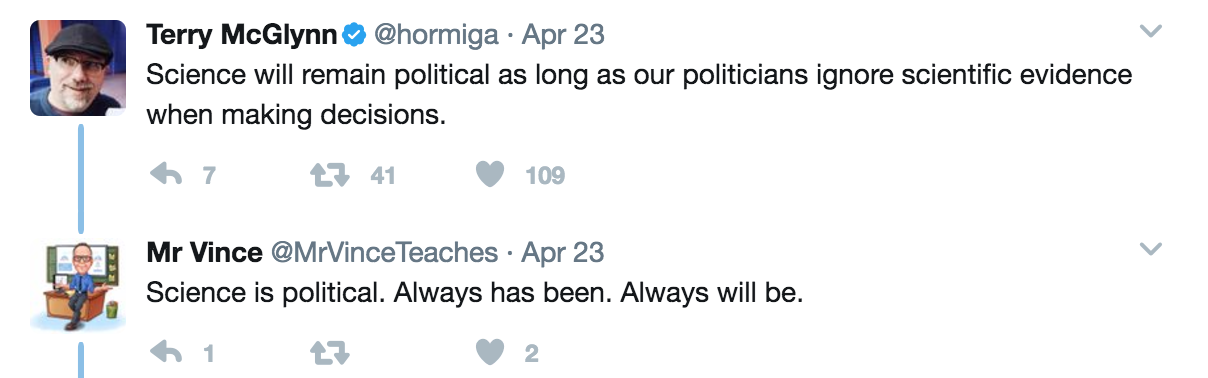

To the surprise of precisely 0 people, I fall into the academic camp when I talk about politics. But I also recognise it’s not a definition that is widely understood within science, for a whole range of reasons. Some are societal - a lot of scientists are people who don’t have to think about power structures, because their demographics put them at the top of em. Others are pedagogical - STS and similar ‘meta’ fields tend not to feature in most science degrees, and to be perfectly honest, STS people aren’t great at communicating their work a lot of the time. So you get interactions like this, which perfectly encapsulate the problem:

One person is using the coloquial definition; the other, the academic. So you get misunderstanding, crossed wires and no actual learning. This is extremely common, and extremely unfortunate, because I happen to think the academic definiton can be incredibly powerful as a lens in improving how we work as scientists and live as people. So I wrote this little guide, roughly divided into ‘what STS and social sciences people mean by “political”’ and ‘why this can be incredibly useful in science’.

What STS means by political

Coloquially, ‘political’ in a scientific context means relating to impacts on science from academic structures. Sometimes this is legislative (NSF funding cuts). Sometimes this is academic (University funding cuts). Whatever the source, it largely means things that help or hinder “scientists’” ability to do their job - whether they can get funding, whether they can get grad students, whether they can get published.

This is certainly an important set of things to be concerned about, but it’s also very narrow. It’s mono-directional - the concern is how society affects science, not how science affects society. It’s also highly constrained even within that - ‘political’ implications for science tend to be funding, hiring, visas, but not Title IX or the ADA, even though those are as legislative and formal as you can get, and if your concerns are about implicit structures, forget it.

In an academic sense, ‘political’ means something much wider - it means “does this involve acquiring, losing or applying power?” Title IX is political - not because it’s a piece of law but because it provides tools for individuals and organisations to challenge sexual assault, misogyny and bias in a university setting. It alters the balance of power. Visa reductions aren’t political just because they impact the ability of scientists to recruit the best grad students, and thus impact the progress of science, but also because they shift opportunities (and so power) away from non-US students, many of them people of colour, and towards American citizens and residents.

Using the academic definition also means thinking about implicit structures. With or without the presence of Title IX, sexual harassment and assault on campus is included as a ‘political’ problem, because it’s something systemic that ties into dominance, bias and, you’ve guessed it, power. So too is racism, ableism, and anything else which (written down or not) has implications for who can work, and under what conditions.

Beyond in-university situations, thinking about things in terms of power also means having a framework to think about where scientists’ authority and resources come from. In a North or South American context, this means thinking about which indigenous peoples’ land was stolen - who was disempowered - to make up the university’s campus. Where is that people now, and what involvement do they have in the work we are doing on their land? It means thinking about research ethics: what are the power dynamics, between researchers and research subjects, in our work, or the work we are building on? Title IX is political, yep, but so is the case of Henrietta Lacks.

Finally, unlike the coloquial definition, which largely looks at the impact society has on science, politics-as-power requires us to examine the impact our work has on society. Who is empowered, or disempowered, by the research we perform? What are the impacts when research using facial structure to measure purported criminality hits implementation, and has our understanding of those impacts informed how we go about double, triple and quadruple-checking that work, and how we go about reporting it? What does it mean when we do work for DARPA, or for oil companies? Where does that work end up?

How this can help science

If you’re still reading and didn’t already know this stuff, I’ll hazard a guess that you’re swirling slightly. That’s entirely understandable - it sounds a lot like ‘political’ covers pretty much everything, which (if your work has any kind of impact) is true. It probably sounds like this is massively overcomplicating things: we’ve gone from engaging with universities or politicians to talking about research ethics and decolonisation.

Absolutely, the academic definition is wider than the coloquial - but I’d argue it actually simplifies things. See, none of the stuff covered by the new definition is actually new. Many of us are already talking about sexual harassment, institutional racism and other forms of bigotry. Research ethics and decolonisation are, as problems, nothing new. Using the academic definition simply gives us a common language for talking about all of these problems - and recognising that however far apart many of them may seem to be, they’re symptoms of the same underlying disease.

Past that, being able to think about these problems as part of the same system wards us against discounting one set of issues entirely to focus on another - precisely as many critics of the Science March have (correctly) felt the March has been doing - and protects us from being caught entirely by surprise by new, future problems. If we approach things systemically, the tools we build to address each issue overlap, and can be adapted.

So in my (exceedingly humble) opinion, the academic definition isn’t some wanky theory term, and isn’t a pedantic destraction from the conversations we’re having - it’s a valuable tool for how we think about problems facing, caused by, and within science. It’s got a lot of utility. I hope that some of you now agree with me - and even if you don’t, conversations about these issues might now make a little more sense to all involved.